One of the strengths of WebXPRT is that it’s a remarkably easy benchmark to run. Its upfront simplicity attracts users with a wide range of technical skills—everyone from engineers in cutting-edge OEM labs to veteran tech journalists to everyday folks who simply want to test their gear’s browser performance. With so many different kinds of people running the test each day, it’s certain that at least some of them use very different approaches to testing. In today’s blog, we’re going to share some of the key benchmarking practices we follow in the XPRT lab—and encourage you to consider—in order to produce the most consistent and reliable WebXPRT scores.

We offer these best practices as tips you might find useful in your testing. Each step relates to evaluating browser performance with WebXPRT, but several of these practices will apply to other benchmarks as well.

- Test with clean images: In the XPRT lab, we typically use an out-of-box (OOB) method for testing new devices. OOB testing means that other than running the initial OS and browser version updates that users are likely to run after first turning on the device, we change as little as possible before testing. We want to assess the performance that buyers are likely to see when they first purchase the device and before they install additional software. This approach is the best way to provide an accurate assessment of the performance retail buyers will experience from their new devices. That said, the OOB method is not appropriate for certain types of testing, such as when you want to compare largely identical systems or when you want to remove as much pre-loaded software as possible. The OOB method is less relevant to users who want to see how their device performs as it is.

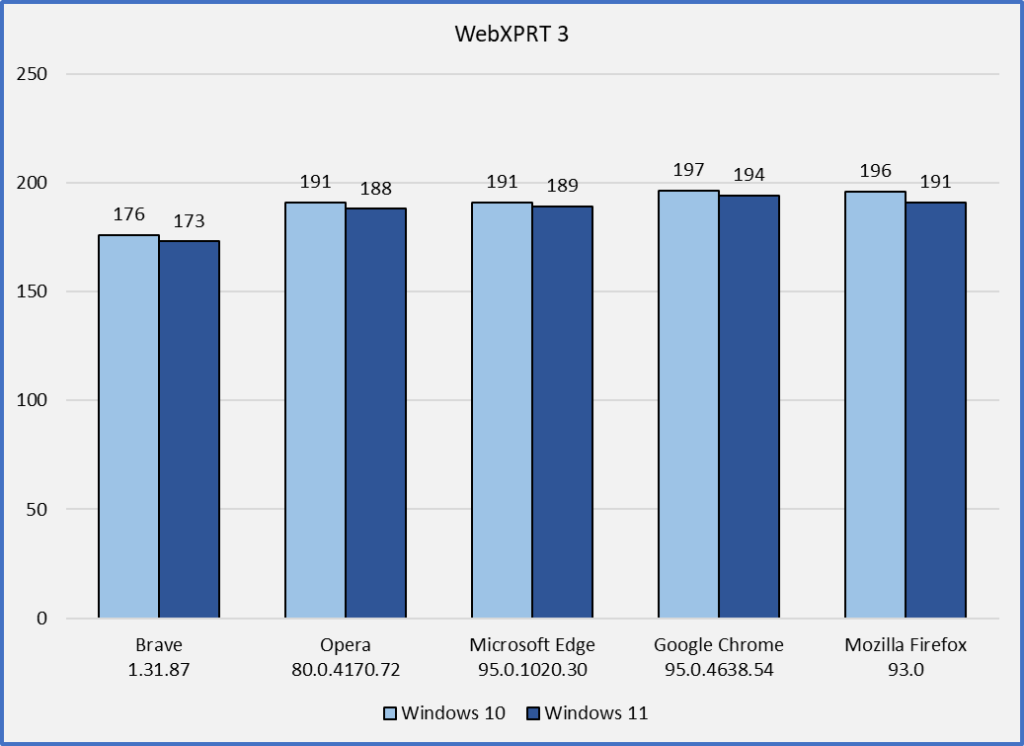

- Browser updates can have a significant impact: Most people know that different browsers often produce different performance scores on the same system. They may not know that there can be shifts in performance between different versions of the same browser. While most browser updates don’t have a large impact on performance, a few updates have increased (or even decreased) browser performance by a significant amount. For this reason, it’s always important to record and disclose the extended browser version number for each test run. The same principle applies to any other relevant software.

- Turn off automatic updates: We do our best to eliminate or minimize app and system updates after initial setup. Some vendors are making it more difficult to turn off updates completely, but you should always double-check update settings before testing. On Windows systems, the same considerations apply to turning off User Account Control notifications.

- Let the system settle: Depending on the system and the OS, a significant amount of system-level activity can be going on in the background after you turn it on. As much as possible, we like to wait for a stable baseline (idle time) of system activity before kicking off a test. If we start testing immediately after booting the system, we often see higher variance in the first run before the scores start to tighten up.

- Run the test more than once: Because of natural variance, our standard practice in the XPRT lab is to publish a score that represents the median of three to five runs, if not more. If you run a benchmark only once and the score differs significantly from other published scores, your result could be an outlier that you would not see again under stable testing conditions or over the course of multiple runs.

- Clear the cache: Browser caching can improve web page performance, including the loading of the types of JavaScript and HTML5 assets that WebXPRT uses in its workloads. Depending on the platform under test, browser caching may or may not significantly change WebXPRT scores, but clearing the cache before testing and between each run can help improve the accuracy and consistency of scores.

We hope these tips will serve as a good baseline methodology for your WebXPRT testing. If you have any questions about WebXPRT, the other XPRTs, or benchmarking in general, please let us know!

Justin